This blog post is part of an occasional series about the Gibson House Museum Archives, a repository of personal documents and photographs from the Gibson family. The archives are accessible by appointment; contact mgholmes@thegibsonhouse.org to make arrangements.

“I said that although I had always thought that it might be best to resume work in Anesthesia on a moderate scale, that you had absolutely declined to have me do this and that I had definitely made up my mind to be guided by you in the matter, and that of course if you did not want me to do it and would not stand for it, that settled it.

. . .

I will now follow your advice and take a rest before the walk which I hope will take place.

I am, darling little Wesscat, with more love and gratitude than I ever felt before in my life, and many kisses for your sweet little self,

Your affectionate husband

Freeman”

|

| Gibson House Museum Archives. |

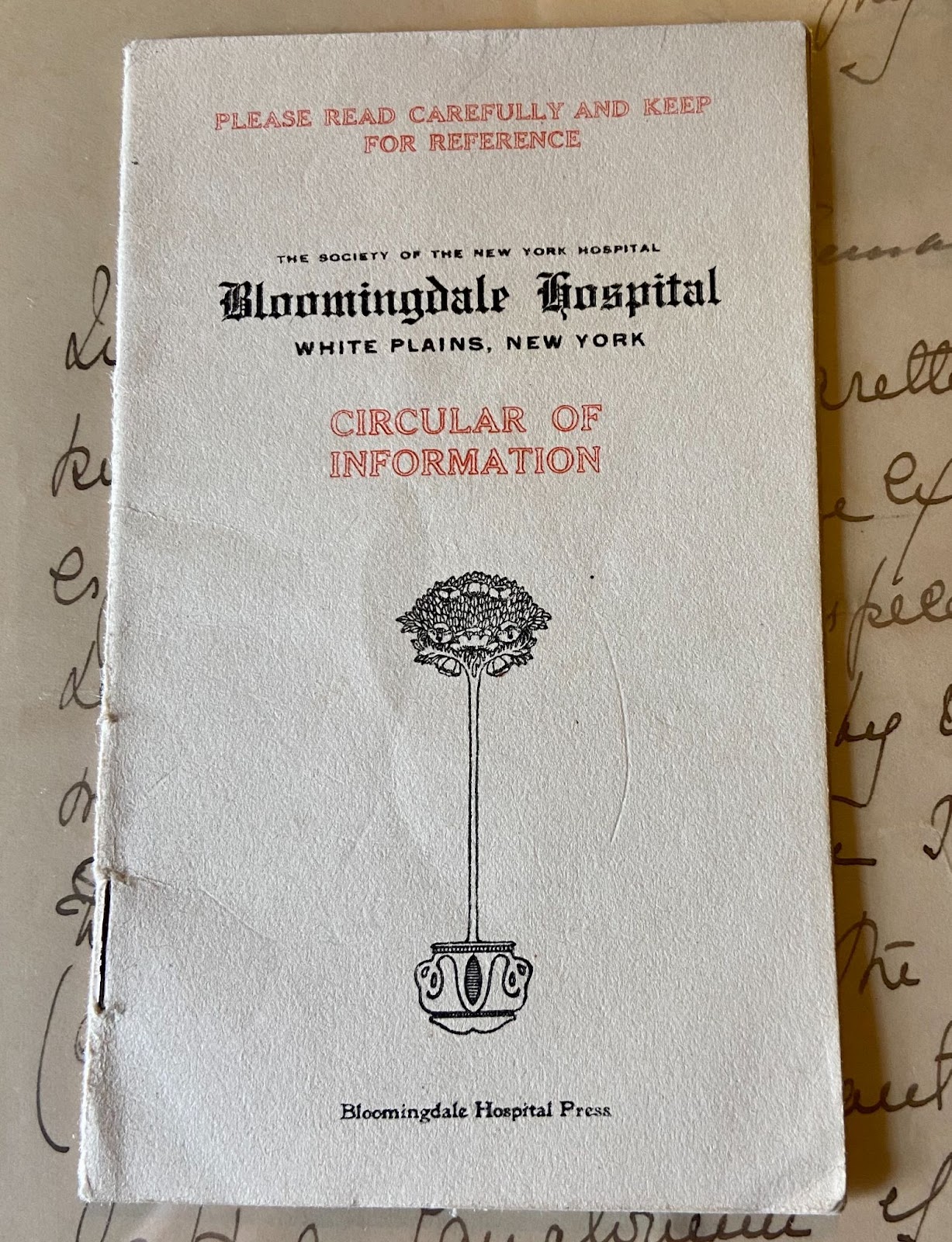

Dr. Freeman Allen wrote these words to his wife, Mary Ethel Gibson Allen, in 1926 while he was a patient at Bloomingdale Hospital in New York. A physician and pioneer in the anesthetics field, Freeman suffered from depression and narcotic addiction, and he spent the last five years of his life being treated in institutions. Throughout it all, he wrote letters to his wife, updating her on his health as well as relaying mundane matters like requests for bowties and candies. As an intern at the Gibson House Museum this spring, I was tasked with reorganizing the over 400 letters that comprise the Mary Ethel Gibson Allen and Dr. Freeman Allen correspondence sub-series. The letters span thirty-six years, starting with their over decade-long courtship and ending with his death by suicide in 1930. The true story of his death was discovered by the museum just a handful of years ago; this revelation is recounted in a blog post here. My work in the archives this semester allowed me to follow Freeman and Mary Ethel’s relationship from its timid beginnings to its resilience in the face of illness and shame. In referencing a book he was reading, Freeman wrote to his wife that “[t]he man committed a worse crime than mine and yet it was a more manly one. If I can possibly succeed in this treatment I shall have expiated my crimes to the best of my ability. . . . I think in your letters you had better make frequent and explicit references to my sins.” Freeman’s feelings of guilt are clear in his letters. He was ashamed to return to the medical field, and he seemed equally ashamed to return to his wife. He felt his mental state was unmanly; indeed, drug use and addiction in the 1920s was seen as feminine. Contemporary public health officials claimed that opiates made users idle and enhanced "the desire to live at the expense of others and by anti-social means.” Being treated in a hospital while his wife was home taking care of their son and dutifully supporting his treatment, he likely felt that he was upsetting the bourgeois gender roles he was raised with. Furthermore, Freeman was one generation removed from the era in which the face of morphine and opium addiction was middle- and upper-class white women. Opiates were frequently prescribed by physicians for “feminine” maladies, such as dysmenorrhea, headaches, and nervous disorders. Freeman’s own mother, Georgiana Stowe, became addicted to morphine after being prescribed the drug following her son’s birth.

Modern psychiatry was still in its infancy when he sought treatment, but Freeman understood that his issues stemmed from a medical disorder. In 1926, Freeman wrote to his wife that “however disgraceful it may be . . . it is a nervous breakdown and is a disease and must be treated, and this essential fact is what I have been losing sight of right along. As you say I must recognize that I am ill, and am being treated radically for a serious trouble.” Psychiatry has advanced significantly over the last century, and depression and substance abuse are widely understood to be disorders instead of moral failings.

|

Mary Ethel and Freeman at 40 Steps, Nahant

Gibson House Museum (1992.470.81) |

While we only have a few of her letters, it is clear that Mary Ethel wrote to her husband loyally and offered advice and support throughout his final years. Freeman wrote often of how “grateful” he was for her letters and closed his correspondence with tender words such as “Goodnight Wesscat/With much love and kisses I am/Your loving/FREEMAN.” He commonly addressed his wife as Wessiecat, and Mary Ethel addressed her husband as Robbie Rat. I grew invested in Wessiecat and Robbie Rat’s relationship while reading their abundance of letters, and I felt quite emotional reading Freeman thanking Mary Ethel “for all [her kindness]” in his final letter.

I hope my contribution to the collection will aid future researchers. While a large portion of the letters date from Freeman’s final years, their correspondence spans over three decades. The couple regularly wrote to each other whether they were across town in Boston, travelling across the country to California, or mountain climbing in Switzerland. The letters are an amazing insight into the experience of a man suffering from depression and addiction in early 20th century America. In addition, it is a story of love both in sickness and in health.

- Anna Boyles (Spring 2021 Curatorial Intern, Simmons University)

To learn more:

- David T. Courtwright, "Addiction to Opium and Morphine" in Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

- Mara L. Keire, "Dope Fiends and Degenerates: The Gendering of of Addiction in the Early Twentieth Century,” Journal of Social History, Vol. 31, No. 4 (Summer, 1998).

No comments:

Post a Comment